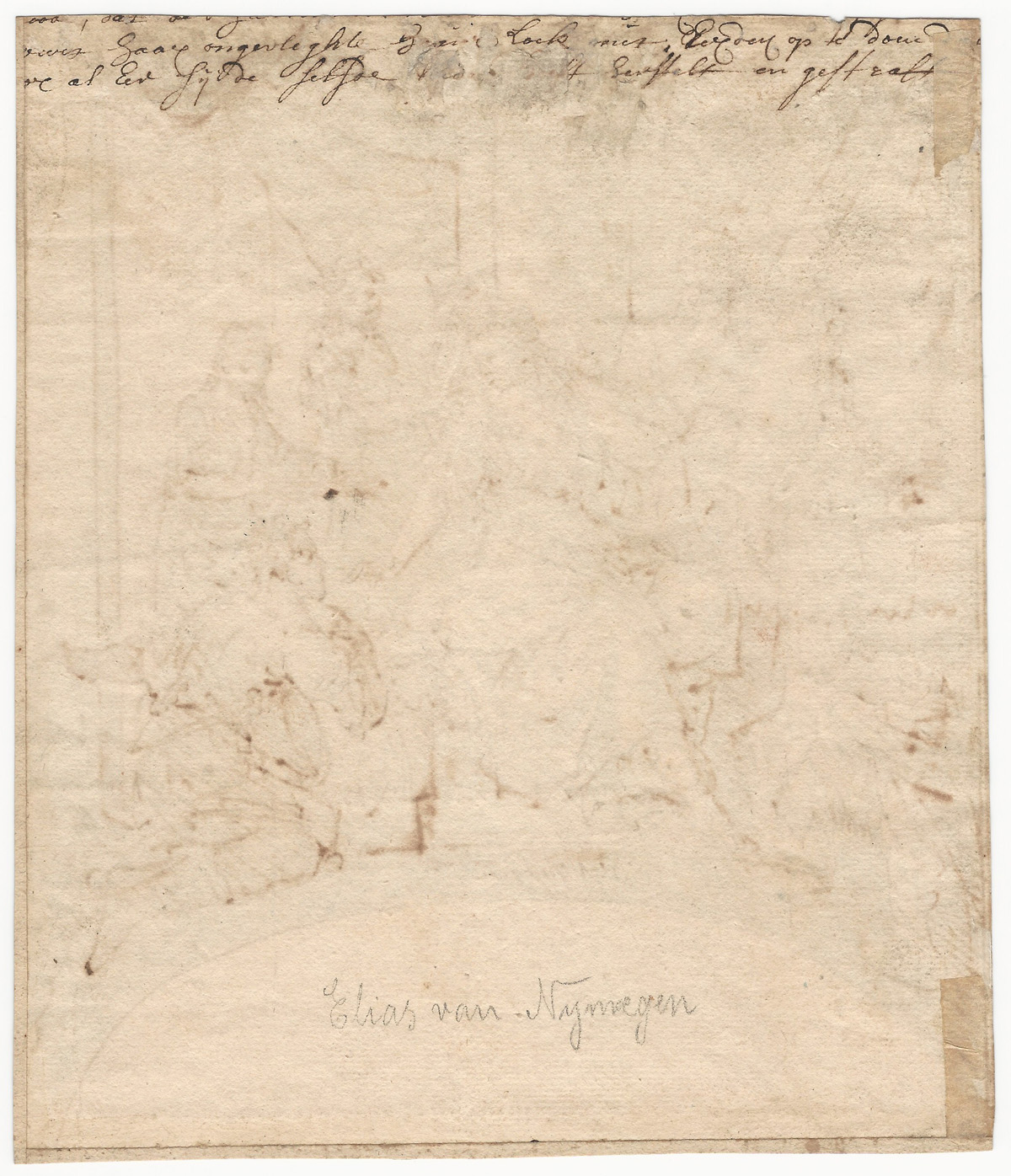

ELIAS VAN NIJMEGEN (Nijmegen 1667 – 1755 Rotterdam)

Elias van Nijmegen (Nijmegen 1667 – 1755 Rotterdam)

Semiramis Receiving News of the Revolt of Babylon: Design for a Chimney Piece

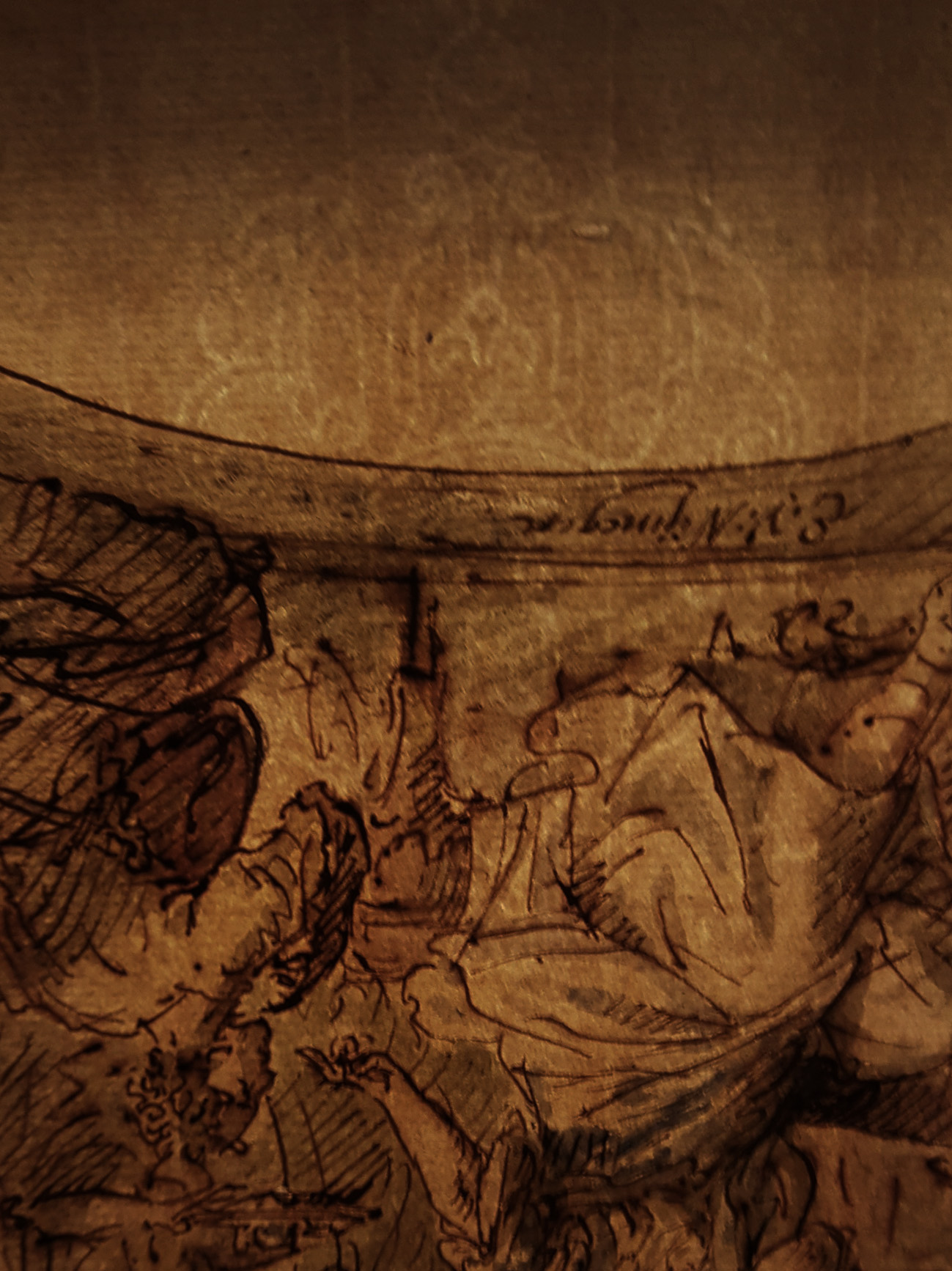

Pen and brown ink, watercolour, watermark Arms of Amsterdam, 211 x 183 mm (8.3 x 7.2 inch)

Signed ‘E. v: Nijmegen’

Provenance

Private collection, Germany

***

Elias was the son of the marble-painter Herbert van Nijmegen, who died when Elias was only twelve.1 He was trained by his elder brothers in painting decorative schemes of flowers and ornamental vases for ceilings and other interior decorations. In 1689 Elias became a member of the Leiden Guild of St Luke, and in 1694 he executed decorative paintings for the Princess of Orange at the Stadtholderly court in Leeuwarden. He established his studio in Rotterdam and married Johanna Stierman there in 1701 and was Dean of the Guild of St Luke from 1702 to 1740. Their son Dionys van Nijmegen (1705–1798) was trained by his father and collaborated on decorative schemes with him, including ceilings and overdoors decorated for the palatial mansion of Gouda’s burgomaster Willem van Strijen on the Westhaven canal, which survive in situ.

By an extraordinary survival, a large group of some 320 drawings and designs by the Van Nijmegen studio remained together, comprised of some 250 drawings and one sketchbook, and was purchased by the Rijksprentenkabinet of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam in 1968.2 It is the only ensemble of such designs from a single studio practice to have survived from this period. The drawings by Elias are almost invariably executed in pen and brown ink and embellished with coloured washes. His handling is highly recognisable, particularly quick and rather angular and nervous, though his finished painted were executed in a smooth manner.

Only a small number of Elias’s drawings in the Rijksmuseum are signed, in lettering very comparable to the signature on our sheet. Our particularly impressive drawing can for instance be compared to the signed drawing of an allegory of History taught by Truth (fig.).3 The semicircular lower edge of our drawing suggests this was a design for a chimney piece painting, with a mirror placed underneath, which was usually part of a larger painted scheme, with other paintings placed in carved mouldings above doors and in ceilings. A typical example of a painted work by Elias van Nijmegen is the Antiochus and Stratonice in the Museum Rotterdam (fig.).4

This scene has only recently been identified as Queen Semiramis receiving the news of the revolt of Babylon: of legendary beauty, Semiramis was one of the founders of the Assyrian empire of Niniveh. Interrupted at her toilette by the news of a revolt, the warrior-queen demonstrated her determination as a ruler by refusing to finish combing her hair until the rebels had been defeated by her armies. The subject was rarely depicted by Dutch artists – or at least few scenes are identified today.

1. For the artist, see: J.W. Niemeijer, ‘De ateliernalatenschap van het Rotterdamse schildersgeslacht Van Nijmegen’, Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 17 (1969), pp. 59-111; The James A. de Rothschild bequest at Waddesdon Manor. Drawings for architecture, design and ornament, London 2006, pp. 683-86; P. Bakker, ‘Crisis? Welke crisis? Kanttekenigen bij het economisch verval van de schilderkunst in Leiden na 1660’, De zeventiende eeuw 27 (2011), pp. 232-69; p. 250; J. van Vught (red.), ‘Nijmeegse biografieën. Deel 3’, Jaarboek Numaga 60 (2013), pp. 11-151.

2. See Niemeijer, op. cit.

3. Pen and brown ink, coloured washes, 233 x 190 mm, inv. no. RP-T-1968-265.

4. Oil on canvas, 319 x 263 cm, Museum Rotterdam, inv. no. 11226.